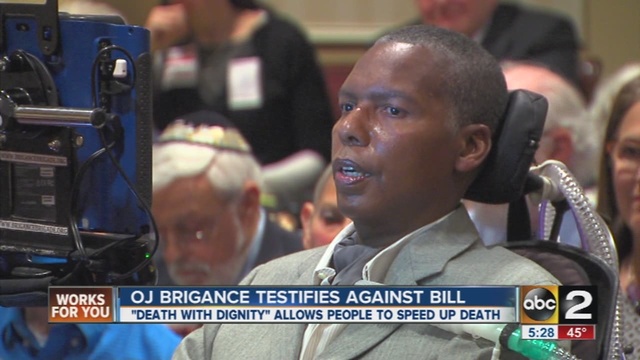

“The thought that there would be a legal avenue for an individual to take his or her own life in a moment of despair, robbing family, friends and society of their presence and contribution to society deeply saddens me and is a tragedy.”

Former Ravens linebacker O.J. Brigance, who is credited with the first tackle in Super Bowl XXXV, which his Baltimore Ravens went on to win 34-7.

Brigance has been battling ALS – also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease – for eight years. A 2001 Super Bowl champion, Brigance is now confined to a wheelchair. He urged lawmakers to reject Maryland’s Death With Dignity Act, introduced by Sen. Ron Young and Del. Shane Pendergrass, both Democrats.

The bill would allow people to end their lives if they are given a terminal diagnosis. Critics testifying before the state’s lawmakers said a physician-assisted suicide bill would prey on those who are vulnerable or disabled.

The legislation, Mr. Brigance wrote, would “devalue the lives and possible future contributions of Marylanders.”

Brigance was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in 2007. Although living with the disorder required major lifestyle adjustments, he now embraces life fully and even leads an organization called the “Brigance Brigade,” which offers grants to families living with the disease. The organization has provided, among other benefits, assistance ramps, wheelchairs and communication devices to those in need.

When the football player heard that a right-to-die bill, which would allow terminally ill patients to obtain a lethal dose of a drug from a doctor, was making its way through the Maryland legislature, he knew he had to try and block its path.

“…valuable contributions can still be made in life, despite one being diagnosed with a terminal illness,” said Brigance, whose public seven-year fight against ALS has made the former star and current Ravens front-office staffer both a national advocate for people with the neurodegenerative disease and an inspiration to the team.

“I don’t think legislation should be approved to legally take a life before the appointed time,” he said.

“Because I decided to live life the best I could, there has been a ripple effect of goodness in the world,” Brigance said. “Since being diagnosed, I have done a greater good for society in eight years than in my previous 37 years on earth.”

Maryland is one of around a dozen states considering right-to-die legislation this year.

States considering similar measures include Alaska, California, Connecticut, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin. The District of Columbia is also debating a bill.

Oregon, Vermont and Washington have legalized medically assisted suicide; courts in Montana and New Mexico have ruled in favor of it.

Speaking with the help of a machine while sitting in a wheelchair, Brigance stated in his testimony against the ‘Death With Dignity Act,’ “…adverse circumstances in no way delete purpose or destiny in one’s life. I don’t know how many days I have left to live, but each and every one has a purpose.”

Although his life is much different than it was a decade ago, Brigance argues it is one that is still worth preserving. Others living with disabilities agree with the football player.

Ryan Anderson of The Heritage Foundation’s Institute for Family, Community and Opportunity argued, “Allowing physician-assisted suicide would be a grave mistake for four reasons. First, it would endanger the weak and vulnerable. Second, it would corrupt the practice of medicine and the doctor–patient relationship. Third, it would compromise the family and intergenerational commitments. And fourth, it would betray human dignity and equality before the law. Doctors should help their patients to die a dignified death of natural causes, not assist in killing. Physicians are always to care, never to kill.”