The following is an excerpt from OpinionJournal.com’s “Best of the Web” written by the editor, James Taranto.

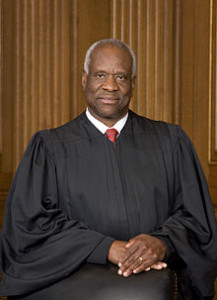

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas

Blintz Krieg

If you follow the Supreme Court, you probably know that Justice Clarence Thomas hardly ever asks questions during oral argument. If you follow the court closely, you may know that Thomas often gives speeches, and that he has publicly explained his reticence on the bench. In April 2012 the Associated Press recounted one such speech, at the University of Kentucky:

Thomas suggested his loquacious colleagues should do more listening and less talking.

“I don’t see where that advances anything,” he said of the questions. “Maybe it’s the Southerner in me. Maybe it’s the introvert in me, I don’t know. I think that when somebody’s talking, somebody ought to listen.” . . .

He said the lawyers presenting their cases are capable and don’t need guidance from the justices: “I don’t need to hold your hand, help you cross the street to argue a case. I don’t need to badger you.” . . .

Thomas said it’s become habit for justices to interrupt lawyers.

“We have a lifetime to go back in chambers and to argue with each other,” he said. “They have 30, 40 minutes per side for cases that are important to them and to the country. They should argue. That’s a part of the process.

“I don’t like to badger people. These are not children. The court traditionally did not do that. I have been there 20 years. I see no need for all of that. Most of that is in the briefs, and there are a few questions around the edges.”

Evidently Jeffrey Toobin disagrees. On Friday Toobin, who writes about the court for The New Yorker, posted a blog item inveighing against what the headline called “Clarence Thomas’s Disgraceful Silence.” We say “evidently” he disagrees because he doesn’t acknowledge, much less respond to, Thomas’s account of his own behavior. Instead Toobin sets out to stigmatize Thomas as some sort of deviant.

One device Toobin uses is to declare that “Thomas’s colleagues [are] best viewed in pairs”–assigned, arbitrarily, by Toobin. One such couple consists of George W. Bush’s nominees and one of Barack Obama’s, but Toobin mixes up the Reagan and Clinton justices, so that Antonin Scalia is paired with Ruth Bader Ginsburg (“the two oldest Justices,” both of whom lived in New York as youngsters) and Anthony Kennedy with Stephen Breyer (who “both sit in similar ways,” have bald heads, and were born in Northern California).

Why not pair Scalia and Samuel Alito, a fellow Italian-American native of Trenton, N.J.? Or Scalia and Kennedy, the only sitting justices to be confirmed unanimously? Or Thomas and Sonia Sotomayor, both Yale Law School graduates with minority ethnic backgrounds, and the only justices to have been divorced?

That last hypothetical question holds the answer to them all. Pairing Justice Thomas with any of his colleagues would defeat the purpose of the exercise, which is to end up with him as the odd man out. It’s like a round of musical chairs with the outcome rigged in advance.

It’s true enough that Thomas is an outlier in declining (with rare exceptions) to participate in oral arguments. Toobin does not suggest, as some other commentators have over the years, that Thomas’s reticence reflects a lack of intelligence or competence. To the contrary, he acknowledges that “for better or worse”–which means, in Toobin’s view, for worse–“Thomas has made important contributions to the jurisprudence of the Supreme Court.” In particular, he describes Thomas as “the intellectual godfather” of the landmark cases Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission (2010) and District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), which expanded Americans’ rights under the First and Second Amendments respectively.

All of which raises the question: So what? Why should it bother anybody, as it bothers Toobin very much, that Thomas generally begs off on asking questions in oral arguments? In answering that question, Toobin invokes (though he does not credit) Immanuel Kant:

Imagine, for a moment, if all nine Justices behaved as Thomas does on the bench. The public would rightly, and immediately, lose all faith in the Supreme Court. Instead, the public has lost, and should lose, any confidence it might have in Clarence Thomas.

Which reminds us of a scene in the 1975 movie “Love and Death.” Sonja (Diane Keaton) and Boris (Woody Allen) are discussing a plan to assassinate Napoleon. Boris is anxious. “Sonja, Sonja, I’ve been thinking about this,” he says. “It’s murder. What if everybody acted like this? It’d be a world full of murderers. You know what that would do for property values?”

“I know,” Sonja retorts. “And if everybody went to the same restaurant on the same day and ordered blintzes, there’d be chaos. But they don’t.”

To which Boris says: “I’m talking about murder, she’s talking about blintzes.”

Well, Toobin is talking about blintzes. He seems to be under the misapprehension that he’s talking about murder.

Toobin’s descriptions of Thomas reflect either obsessively close observation or flights of imagination, perhaps both. According to Toobin, Thomas “projects a different kind of silence than he did earlier in his tenure”:

In his first years on the Court, Thomas would rock forward, whisper comments about the lawyers to his neighbors Breyer and Kennedy, and generally look like he was acknowledging where he was. These days, Thomas only reclines; his leather chair is pitched so that he can stare at the ceiling, which he does at length. He strokes his chin. His eyelids look heavy. Every schoolteacher knows this look. It’s called “not paying attention.”

The assumption that Thomas is “not paying attention” is unwarranted. Perhaps he’s looking toward the ceiling, or reclining with his eyes closed, while listening intently. The court issues audio recordings of its oral arguments (as well as transcripts), but not video. Not for nothing are legal proceedings called “hearings” rather than “shows.”

As noted above, Thomas has said he declines to participate in oral arguments out of politeness. Even if one holds to the uncharitable view that it is a form of hauteur, it’s not as if the other justices treat the lawyers before them with deference. Justices frequently interrupt lawyers by asking them questions, preventing them from finishing their opening arguments or their answers to other justices’ questions.

That would be shockingly rude in a meeting among equals. But a Supreme Court proceeding is not such a meeting. The justices’ domination of the arguments and the lawyers’ obeisance reflect the actual distribution of power in the room. The lawyers well understand they are in a supplicant role. If Thomas’s silence is in fact disdainful, as Toobin believes, it is just a different way of expressing dominance.

Toobin’s likening of Thomas to a defiant schoolboy is altogether inappropriate. Who exactly is the “schoolteacher” toward whom we are supposed to imagine Thomas is insubordinate? The lawyers whose cases are before the court? No, he (like the other justices) is in a superior position to them. The other justices? No, each of them is Thomas’s equal.

The position of Supreme Court justice is unusual in that it is one of the few institutional roles in which one is subordinate to nobody. Like other federal judges, the justices do not answer to the voters or, once confirmed, to the political branches of government (except in the rare case of impeachment). Unlike other federal judges, their work is not subject to review by a higher court. The chief justice, or sometimes a senior associate justice, has the procedural authority to assign the writing of a majority opinion. But no justice is compelled to join such an opinion. Each is free to vote as he sees fit and to express his own views in concurrence or dissent.

What is it about Thomas that leads Toobin to believe that he, apparently alone among the justices, has a duty to be submissive? Or perhaps we should ask: What is it about Toobin?

For more “Best of the Web” click here and look for the “Best of the Web Today” link in the middle column below “Today’s Columnists.”