The following is an excerpt from OpinionJournal.com’s “Best of the Web” written by the editor, James Taranto.

The Bad News is Wrong

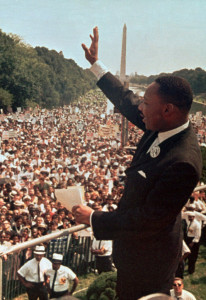

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. giving his “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963 in Washington, D.C.

This week marks the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which is known today primarily as the occasion of Martin Luther King’s magnificent “I Have a Dream” speech. Such anniversaries generate a great deal of mundane commentary to the following effect: There is no denying we made significant strides toward equality since Dr. King spoke, but we still have a long way to go, and enacting my preferred policies will help us get there.

The weakness in such a line of thinking is the assertion that “we still have a long way to go.” Perhaps such an assertion was plausible in 1973, or even 1983. But it’s 2013 and a black man is president of the United States. Is it remotely possible that the glass is still half empty?

Only if you can’t tell the difference between water and air (or if you obscure it deceptively). Consider this passage from a gloomy weekend column by Charles Blow of the New York Times:

We appear to be resegregating–moving in the opposite direction of King’s dream.

The Great Migration–in which millions of African-Americans in the 20th century, in two waves, left the rural South for big cities in the North, Midwest and West Coast–seems to have become a failed experiment, with many blacks reversing those migratory patterns and either moving back to the South or out of the cities.

As USA Today reported in 2011:

“2010 census data released so far this year show that 20 of the 25 cities that have at least 250,000 people and a 20 percent black population either lost more blacks or gained fewer in the past decade than during the 1990s. The declines happened in some traditional black strongholds: Chicago, Oakland, Atlanta, Cleveland and St. Louis.”

The Great Migration occurred between 1910 and 1970, the two waves separated by a lull in the 1930s caused by the Great Depression. Non-Southern cities offered both economic opportunity and relief from Jim Crow segregation. But the movement back to the South has been going on for decades, as William Frey noted in a 2004 Brookings Institution Report, “The New Great Migration: Black Americans’ Return to the South, 1965-2000.”

Frey looks at black migration patterns in the latter half of each decade between the 1960s and the 1990s. Between 1965 and 1970, at the end of the old Great Migration, the 10 states with the largest net increases in black population were all outside the South (they included one border state, Maryland).

The 9 states with the largest net decline were all in the South; of the 11 former Confederate states, only Florida and Texas didn’t make the list. (It’s 9 states because the District of Columbia is in the bottom 10.)

The reversal was already well under way by 1975-80. Although California still topped the list of states gaining black residents, the top 10 included 6 Southern states, 4 of which had been in the bottom 10 a decade earlier: Texas, Georgia, Virginia, Florida, North Carolina and South Carolina. New York, meanwhile, took the bottom spot, which it also held in 1985-90 and 1995-2000. By the late ’70s only 3 Southern states remained in the bottom 10: Mississippi, Arkansas and Alabama.

By 1985-90, California had dropped to 6th place for black net in-migration; 4 of the top 5 states were in the South, with Georgia at No. 1.

In 1995-2000, 7 of the top 10 spots belonged to Southern states, with Georgia still on top. California had dropped from 6th place to 50th out of 51–that is, just below New York on the list of states with the biggest net losses of black population. Louisiana was the only Southern state in the bottom 10, making its first appearance on that list since 1965-70.

To sum up the reversal: Of the top 10 states for black in-migration in 1965-70, 5 were in the bottom 10 three decades earlier. And of the top 10 states for black in-migration in 1995-2000, 5 had been in the bottom 10 three decades earlier.

There was only one constant throughout the study: In all four of the half-decade periods studied, Maryland was one of the top 10 states gaining black population and the District of Columbia was among the 10 states with the greatest losses. Among metropolitan areas, Washington-Baltimore was among the top 10 gainers in all four periods. That suggests a pattern of black flight from central cities to suburbs, one that is otherwise obscured in a state-level population analysis.

Now, why would blacks move out of big cities in the Northeast, the Midwest and California and into the South and the suburbs? In part for the same reasons nonblacks do: in search of better economic opportunities and quality of life. But also because the factor that drove blacks in particular to leave the South no longer exists. Jim Crow is now long dead, but it had been dead a decade at most by the time the New Great Migration began. As Frey summed it up in 2004:

This full-scale reversal of blacks’ “Great Migration” north during the early part of the 20th century reflects the South’s economic growth and modernization, its improved race relations, and the longstanding cultural and kinship ties it holds for black families. This new pattern has augmented a sizeable and growing black middle class in the South’s major metropolitan areas.

Half a century ago, life was brutally oppressive for blacks in the South. Today the South is the most attractive place for black Americans to live. Charles Blow would have you believe that is bad news about the state of race relations. Who knows, maybe he actually believes such nonsense himself.

For more “Best of the Web” click here and look for the “Best of the Web Today” link in the middle column below “Today’s Columnists.