When Did Soldiers Stop Being Heroes?

Weekly Editorial — Posted on May 20, 2010

(by Kyle Smith, NYPost.com) – Heroes are all around us. Aren’t they? Oprah’s “Heroes in Hard Times” show last May showcased such worthies as Dr. Dan Bell and his wife, Suzie (who run a medical clinic two days a month), Hal Coston (asks people to donate old cars, then fixes them up and sells them for a small fee to the needy), Dale Dunning (soup kitchen), Dallas Gigrich (home heating-oil nonprofit), Tim Nicolai (allows homeless people to stay at his motel), Mary Marzano (collects worn-out bedding from hotels, sends it to homeless shelters).

Nice people. Wonderful people. But heroes?

I don’t even have to tell you that none of Oprah’s chosen heroes was involved in either of the two ongoing wars. You’ve grown used to thinking of “hero” as one of those words that’s mainly used as a metaphor or hype (see also: icon, revolutionary, epicenter). Yet hero is simultaneously over- and under-used.

In civilian life, the definition of hero edges further and further from exploits of daring and closer to the definition of a saint. Today’s hero could go online, set up a service that provides doggie sweaters to the neediest Chihuahuas of the northeast and claim hero status without leaving his desk. But was even Capt. Chesley Sullenberger – though skillful, brave and calm – a hero? Did he voluntarily put himself in harm’s way?

None of Oprah’s “heroes” risked his life. Time magazine does a “heroes of the environment” spectacular, but all of these worthies from Team Green would not have a composting toilet to use without basic security, and there wouldn’t be much of that if we were dependent on the mercy of a medieval, brutality-ruled caliphate. The phrase “heroes of war” hasn’t appeared in Time since 1999 (and that was about the conflict in . . . Bosnia?). Trawl through the recent references to supposed heroes in Time.com and you’ll see a lot of references to “Survivor” and Hayden Panettiere.

Actual heroes? No one much cares.

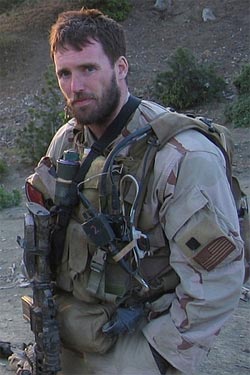

Michael Murphy was a Long Island kid from Patchogue who wanted to help people on a grand scale. Once he leapt out of bed at 3:30 to drive down the New Jersey turnpike and give a stranded friend a ride. “Michael believed doing for others was a life well lived for him,” says his father, Dan Murphy, a lawyer in Suffolk Country. “That’s why he became a lifeguard, that’s why he became a tutor, that’s why he joined the military.” Even by Oprah standards, two out of three ain’t bad.

Michael Murphy was a Long Island kid from Patchogue who wanted to help people on a grand scale. Once he leapt out of bed at 3:30 to drive down the New Jersey turnpike and give a stranded friend a ride. “Michael believed doing for others was a life well lived for him,” says his father, Dan Murphy, a lawyer in Suffolk Country. “That’s why he became a lifeguard, that’s why he became a tutor, that’s why he joined the military.” Even by Oprah standards, two out of three ain’t bad.

Now consider what he did in the military, as a Navy SEAL lieutenant on June 28, 2005, in Afghanistan, where his four-man patrol was attacked by 30 to 40 Taliban. Behind a rock, he couldn’t get reception on his phone – so he scrambled into the path of the gunfire to get a signal and call in air support. He and the Taliban continued their dispute until Murphy and a number of the guerillas were dead. Hospital Corpsman Second Class Marcus Luttrell was the only survivor of the group.

The tale is told in two new books, Luttrell’s “Lone Survivor: The Eyewitness Account of Operation Redwing and the Lost Heroes of SEAL Team 10” (Little, Brown and Co.) and author Gary Williams’ “Seal of Honor: Operation Red Wings and the Life of Lt. Michael P. Murphy, USN” (Naval Institute Press).

In the age of soup-kitchen heroism, I know what you’re thinking. Lt. Murphy was fine on maneuvers, but did his devotion to duty ever extend as far as calling up the local Marriott and asking if he could pick up some old pillowcases?

But let me just draw your attention to three words from the US Navy website.

They are: “two-hour firefight.”

Anyone who has ever been in or even near any kind of danger – a car accident, a shooting – can tell you how time unfurls and stretches out to extravagant, nightmare length. I spent a few weeks in the summer of 1988 stumbling around Ft. Bragg, where young cadets were put through an amusing little drill called the “40-foot rope drop.” You shimmy out on a rope, you let go. You wind up in the waters below. Not a lot more to it than that.

It didn’t sound hard. Plus, as grinning sergeants stood around assuring us, our fall would surely be broken by water moccasins. I let go of the rope and . . . nothing. Falling. Space. Waiting. More falling. The time passed like January. January in Alaska. When, I started to ask myself, would I ever get to where I was going? As I hit, or smashed, the water, the point of the exercise became very clear.

Today I consult Mr. Google to tell me how long my fall took. 1.6 seconds? Can that be possible? One point six seconds, it turns out, can be an ordeal. An epic. And I wasn’t even in real danger.

Lt. Murphy and his squad spent two hours shooting and being shot at. That isn’t a day’s worth of valor. It isn’t even a lifetime’s worth. It’s like the figures you read in a physics textbook about the scope of the universe. It’s beyond our power to comprehend. Luttrell later said Michael was a man of colossal, almost unbelievable courage. He also said that if they built a monument to Lt. Murphy as tall as the Empire State Building, it would never be tall enough.

“We throw the word hero around way too often,” says Michael’s father, Dan, who is himself still partially disabled from a Vietnam War wound. “People will say Tiger Woods is a hero because he can shoot a great golf shot. I think when you attach ‘hero’ to someone using their God-given talents to either play a sport or sing a song, or to a celebrity, it lessens the term.

“I think we ought to reserve the term hero for not only Michael but the man who jumped on a train track just a couple of months ago to save someone. Heroes are people who improve society and put their lives at risk. A policeman, a fireman who runs into a burning building is a hero. A celebrity is not a hero.”

The senior Murphy didn’t even want his son to join the military. He thought it would be a waste of his talents. “Michael always wanted to be the best of the best so when he decided to join the Navy, why did he go into special ops? It was the immediacy. As a Navy SEAL, the impact he could have on defending the United States would be the most acute or the most severe. He could have the greatest impact for the good.”

I first noticed the problem with people’s perceptions of military heroism in 1991, when I and my then-girlfriend were discussing the merits of presidential candidates. I was impressed [when reading about] another Navy SEAL [who] had received the Medal of Honor for his service in Vietnam. …

She replied, “That means no more to me than getting an A on a high-school paper.” [The Navy SEAL] had had part of his right leg destroyed by a grenade when he gave himself a shot of morphine, put a tourniquet on the leg (which was later amputated below the knee), and organized a defense that eventually routed a Vietcong unit in the bay of Nha Trang.

In a depressing way, though, the Oprah view of heroism even has seeped into the military. Only six Medals of Honor have been bestowed in the two current wars – and all six recipients were killed as a result of their bravery. All six received the honor for risking their lives in an attempt to save the lives of their fellow fighting men. (Three of them threw themselves on grenades.)

Is it now unofficial military policy that you may receive the nation’s highest honor only in your casket? In addition to these honorable six, aren’t there many more troops who used great resourcefulness and bravery to kill despicable foes and preserve friendly lives, including their own? No one should be disqualified from the nation’s highest honor for adhering to what I call Patton’s Law: “The object of war is not to die for your country but make the other bastard die for his.”

Patton’s Law doesn’t denigrate the achievement of those who have fallen for their country. Nor is killing the only role of the military. But there is an element of bitter reality to the statement attributed to him.

Now that Oprah leads our moral battles – now that she is our Patton – what future lies in store for a country where the most respected thinkers push the young, the bold and the public-minded into thinking that true service lies in picking up a ladle but not a uniform? The New York Times didn’t even report Lt. Murphy’s story (which was initially classified) until 10 days after President Bush approved the Medal of Honor.

The American pop culture no longer loathes the military the way it did when Jane Fonda was getting handed an Oscar for Best Performance by a Lead Actress in the Role of Supporting the Enemy.

Yet today the culture is almost totally indifferent to the profession of arms. Those who join and fight are simply a curious little subculture with their own mysterious values and traditions, like ham radio operators or the Amish. They can’t compete for attention in a world gone fabulous, and if there is an HBO series about WWII, let us never forget that the real story is Tom Hanks.

“Does it distress me that more people don’t come out to Calverton on Veterans Day or Memorial Day to pay homage?” asks the senior Murphy. “Yes, but I understand people have busy lives.” You get a bonus if you even know that Calverton is a national cemetery – exit 68 off the L.I.E. on your way to the Hamptons. Section 67, grave 3710 is where you will find Lt. Murphy.

He joined the military before 9/11 because he wanted to be the best. After 9/11, he forged a close bond with the firefighters of Engine 53/Ladder 43 in Spanish Harlem. Today the stationhouse proudly displays the unit patch Lt. Murphy was wearing when he fell.

“We really ignore the day-to-day job that these first responders do,” says Dan Murphy, “whether its police, fire, EMTs, military – they don’t ask for glory, they’re out there to serve us.

“If someone just stops and thinks about the fact that we have soldiers, sailors, airmen defending our interest, then I’m satisfied. I’m happy with that.

“If you see policemen on the street, or firemen, or servicemen or women walking down the street, it’s nice to go up to them and say to them, ‘Thank you for your service.’ It would make the world a lot nicer place.”

This article was first in the New York Post on April 25, 2010. Reprinted here on May 20th for educational purposes only. May not be reproduced on other websites without permission from The New York Post. Visit the website at NYPost.com.