FDR’s D-Day Prayer

Weekly Editorial — Posted on June 5, 2014

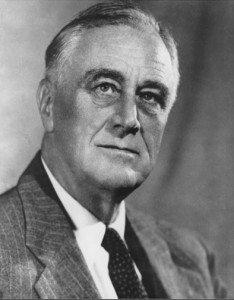

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt

(by Warren Kozak, The Wall Street Journal) – Franklin Roosevelt is not remembered for his religious dogma. Yet [70] years ago on the night of June 6, as tens of thousands of American and Allied forces [landed at Normandy], the president and commander in chief sought to calm an anxious nation as he spoke to his people. It was a presidential address that stands out as a testament to how much our nation has changed since that evening in the late spring of 1944.

Beginning around midnight the night before, elements of the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions had landed behind enemy lines in France. They were followed seven hours later by massive landings on beaches in Normandy code-named Sword, Juneau, Gold, Omaha and Utah.

Americans began hearing special reports in the middle of the night and they continued to follow events closely throughout the day. At lunch counters and in offices and factories, people clustered around their radios. So it was both natural and necessary that the president say something.

Yet instead of giving a news account – something Americans had already heard from network radio news and read in their evening papers – Franklin Roosevelt chose a different course. He led the nation in prayer. He began:

‘Almighty God, our sons, pride of our nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity.

Lead them straight and true; give strength to their arms, stoutness to their hearts, steadfastness in their faith.

There were mothers and fathers listening intently to that broadcast whose sons were already caught up in the middle of it all. Some of those young men were already lost. Roosevelt understood this, yet he never sugarcoated the realities. He continued with his prayer:

They will be sore tried, by night and by day, without rest until victory is won. The darkness will be rent by noise and by flame. Men’s souls will be shaken with the violences of war.

Some will never return. Embrace these, Father, and receive them, thy heroic servants, into thy kingdom.

Somehow, Roosevelt understood what the nation needed to hear. This was an American president unafraid to embrace God and to define an enemy that clearly rejected the norms of humanity. And if the nature of the enemy was not clear to everyone that night, it would be made resoundingly clear as the armies advanced into Germany 10 months later. But Roosevelt also knew that the nation would have to stay true to its course, and for that he offered a moment as well. He also prayed:

Oh Lord, give us faith. Give us faith in thee; faith in our sons; faith in each other; faith in our united crusade. Let not the keenness of our spirit ever be dulled.

With thy blessing we shall prevail over the unholy forces of our enemy. Help us conquer the apostles of greed and racial arrogances.

Americans hung on every word. They needed to rededicate and redouble their efforts, much as Lincoln had reminded them at Gettysburg in the middle of another dark period. Now, almost an equal time has passed since D-Day, and it seems strangely difficult for our leaders to clearly define our values, our way of life, our causes for going to war to defend our ideals. It is unfathomable today that a president would embrace God the way Roosevelt did on that night.

Imagine a president, any president, sitting in the Oval Office ending an address to the nation, in a slow, deliberate cadence, like this:

Thy will be done, Almighty God.

Amen.

Yet that is how Franklin Roosevelt signed off that D-Day night.

(Read President Roosevelt’s entire prayer here and listen to it under “Resources” below the questions.)

Mr. Kozak is the author of “LeMay: The Life and Wars of General Curtis LeMay” (Regnery, 2009). Published June 5, 2012 at The Wall Street Journal. Reprinted here June 5, 2014 for educational purposes only. Visit the website at wsj .com.

Questions

1. Were you surprised to read that President Roosevelt addressed the nation in prayer? Explain your answer.

2. The purpose of an editorial/commentary is to explain, persuade, warn, criticize, entertain, praise or answer. What do you think is the purpose of Warren Kozak's editorial? Explain your answer.

3. Has Mr. Kozak caused you to think differently about an American president leading our nation in prayer? Explain your answer.

[Note: Presidential prayer has been a part of our American history. President Abraham Lincoln quoted the Bible, Psalm 33:12, “Blessed is the nation whose God is the Lord” in his Presidential proclamation during the Civil War, calling for “a day of national humiliation, fasting and prayer.” Is it good that American presidents no longer call on Almighty God for strength, blessing and mercy?]

Background

D-DAY:

- On June 6, 1944, 160,000 Allied troops landed along a 50-mile stretch of heavily-fortified French coastline to fight Nazi Germany on the beaches of Normandy, France.

- General Dwight D. Eisenhower called the operation a crusade in which “we will accept nothing less than full victory.”

- More than 5,000 Ships and 13,000 aircraft supported the D-Day invasion, and by day’s end on June 6, the Allies gained a foot-hold in Normandy.

- The D-Day cost was high – more than 9,000 Allied Soldiers were killed or wounded — but more than 100,000 Soldiers began the march across Europe to defeat Hitler.

(read more at army.mil/d-day)