U.S. Supreme court hears TV broadcasters’ case against Aereo

Daily News Article — Posted on April 23, 2014

(by Mark Sherman, San Jose Mercury News) WASHINGTON (AP) — The Supreme Court is taking up a dispute between broadcasters and an Internet startup company that has the potential to bring big changes to the television industry.

(by Mark Sherman, San Jose Mercury News) WASHINGTON (AP) — The Supreme Court is taking up a dispute between broadcasters and an Internet startup company that has the potential to bring big changes to the television industry.

The company is Aereo, and the justices heard arguments Tuesday over its service that gives subscribers in 11 U.S. cities access to television programs on their laptop computers, smartphones and other portable devices.

The broadcasters say Aereo is essentially stealing their programming by taking free television signals from the airwaves and sending them over the Internet without paying redistribution fees. Those fees, increasingly important to the broadcasters, were estimated at $3.3 billion last year.

The case involving Internet innovation is the latest for justices who sometimes seem to struggle to stay abreast of technological changes.

Broadcasters including ABC, CBS, Fox, NBC and PBS sued Aereo for copyright infringement, saying Aereo should pay for redistributing the programming the same way cable and satellite systems do. Some networks have said they will consider abandoning free over-the-air broadcasting if they lose at the Supreme Court.

Aereo founder and CEO Chet Kanojia recently told The Associated Press that broadcasters can’t stand in the way of innovation, saying, “the Internet is happening to everybody, whether you like it or not.” Aereo, backed by billionaire Barry Diller, plans to more than double the number of cities it serves, although the high court could put a major hurdle in the company’s path if it sides with the broadcasters.

Aereo’s service starts at $8 a month and is available in New York, Boston, Houston and Atlanta, among others. Subscribers get about two dozen local over-the-air stations, plus the Bloomberg TV financial channel.

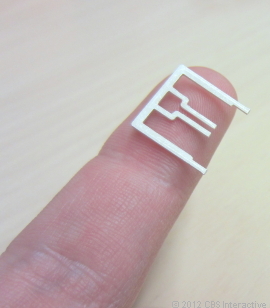

In the New York market, Aereo has a data center in Brooklyn with thousands of dime-size antennas. When a subscriber wants to watch a show live or record it, the company temporarily assigns the customer an antenna and transmits the program over the Internet to the subscriber’s laptop, tablet, smartphone or other device.

In the New York market, Aereo has a data center in Brooklyn with thousands of dime-size antennas. When a subscriber wants to watch a show live or record it, the company temporarily assigns the customer an antenna and transmits the program over the Internet to the subscriber’s laptop, tablet, smartphone or other device.

The antenna is only used by one subscriber at a time, and Aereo says that’s much like the situation at home, where a viewer uses a personal antenna to watch over-the-air broadcasts for free.

The broadcasters and their backers argue that Aereo’s competitive advantage lies not in its product, but in avoiding paying for it.

The federal appeals court in New York ruled that Aereo did not violate the copyrights of broadcasters with its service, but a similar service has been blocked by judges in Los Angeles and Washington, D.C.

The 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New York said its ruling stemmed from a 2008 decision in which it held that Cablevision Systems Corp. could offer a remote digital video recording service without paying additional licensing fees to broadcasters because each playback transmission was made to a single subscriber using a single unique copy produced by that subscriber. The Supreme Court declined to hear the appeal from movie studios, TV networks and cable TV companies.

The 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New York said its ruling stemmed from a 2008 decision in which it held that Cablevision Systems Corp. could offer a remote digital video recording service without paying additional licensing fees to broadcasters because each playback transmission was made to a single subscriber using a single unique copy produced by that subscriber. The Supreme Court declined to hear the appeal from movie studios, TV networks and cable TV companies.

In the Aereo case, a dissenting judge said his court’s decision would eviscerate copyright law. Judge Denny Chin called Aereo’s setup a sham and said the individual antennas are a “Rube Goldberg-like contrivance” — an overly complicated device that accomplishes a simple task in a confusing way — that exists for the sole purpose of evading copyright law.

-The case is ABC v. Aereo, 13-461.

From an Associated Press report. Reprinted here for educational purposes only. May not be reproduced on other websites without permission from the San Jose Mercury News. Visit the website at mercury news .com.

Background

On the Supreme Court from BensGuide.gpo.gov:

- Approximately 7,500 cases are sent to the Supreme Court each year. Out of these, only 80 to 100 are actually heard by the Supreme Court. When a case comes to the Supreme Court, several things happen. First, the Justices get together to decide if a case is worthy of being brought before the Court. In other words, does the case really involve Constitutional or federal law? Secondly, a Supreme Court ruling can affect the outcome of hundreds or even thousands of cases in lower courts around the country. Therefore, the Court tries to use this enormous power only when a case presents a pressing constitutional issue. …

- The Supreme Court convenes, or meets, the first Monday in October. It stays in session usually until late June of the next year. When they are not hearing cases, the Justices do legal research and write opinions. On Fridays, they meet in private (in “conference”) to discuss cases they’ve heard and to vote on them. …

- Most cases do not start in the Supreme Court. Usually cases are first brought in front of lower (state or federal) courts. Each disputing party is made up of a petitioner and a respondent.

- Once the lower court makes a decisions, if the losing party does not think that justice was served, s/he may appeal the case, or bring it to a higher court. In the state court system, these higher courts are called appellate courts. In the federal court system, the lower courts are called United States District Courts and the higher courts are called United States Courts of Appeals.

- If the higher court’s ruling disagrees with the lower court’s ruling, the original decision is overturned. If the higher court’s ruling agrees with the lower court’s decision, then the losing party may ask that the case be taken to the Supreme Court. But … only cases involving federal or Constitutional law are brought to the highest court in the land.

(from supremecourt.gov/visiting/visitorsguidetooralargument.aspx)

- A case selected for argument usually involves interpretations of the U. S. Constitution or federal law. At least four Justices have selected the case as being of such importance that the Supreme Court must resolve the legal issues.

- An attorney for each side of a case will have an opportunity to make a presentation to the Court and answer questions posed by the Justices. Prior to the argument each side has submitted a legal brief – a written legal argument outlining each party’s points of law. The Justices have read these briefs prior to argument and are thoroughly familiar with the case, its facts, and the legal positions that each party is advocating.

- Beginning the first Monday in October, the Court generally hears two one-hour arguments a day, at 10 a.m. and 11 a.m., with occasional afternoon sessions scheduled as necessary. Arguments are held on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays in two-week intervals through late April (with longer breaks during December and February). The argument calendars are posted on the Court’s Website under the “Oral Arguments” link. In the recesses between argument sessions, the Justices are busy writing opinions, deciding which cases to hear in the future, and reading the briefs for the next argument session. They grant review in approximately 100 of the more than 10,000 petitions filed with the Court each term. No one knows exactly when a decision will be handed down by the Court in an argued case, nor is there a set time period in which the Justices must reach a decision. However, all cases argued during a term of Court are decided before the summer recess begins, usually by the end of June.

- During an argument week, the Justices meet in a private conference, closed even to staff, to discuss the cases and to take a preliminary vote on each case. If the Chief Justice is in the majority on a case decision, he decides who will write the opinion. He may decide to write it himself or he may assign that duty to any other Justice in the majority. If the Chief Justice is in the minority, the Justice in the majority who has the most seniority assumes the assignment duty.