Shell Shock: Chinese Demand Reshapes U.S. Pecan Business

Daily News Article — Posted on April 29, 2011

(by David Wessel, The Wall Street Journal, WSJ.com) – Pecans are as all-American as anything can be. Washington and Jefferson grew them. They are the state nut of Arkansas, Alabama and Texas. The U.S. grows about two-thirds of the world’s pecans and chews most of them itself.

For generations, pecan prices have fallen with bumper crops and soared with lousy ones. But lately, they’ve only been going up. A pound of pecans in the shell fetched $2.14 on average last year, according to the U.S Department of Agriculture, nearly double what they brought three years earlier.

The reason: The Chinese want [pecans].

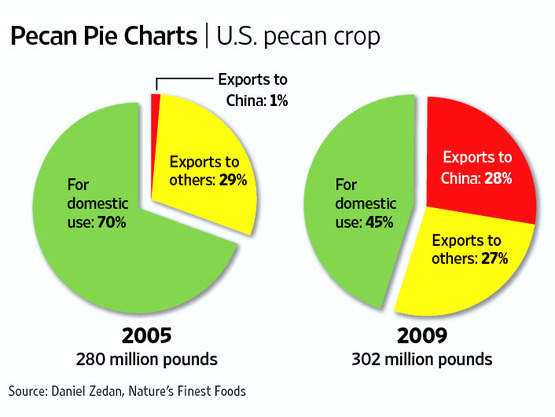

Five years ago, China bought hardly any pecans. In 2009, China bought one-quarter of the U.S. crop, and there’s no sign demand is abating.

At a Carrefour store near Beijing’s Sanyuan Bridge, Liu Wei, a 61-year-old retired chemistry teacher, is buying a 260-gram (9.1-ounce) bag of Orchard Farmer U.S.-grown pecans for 38 yuan ($5.78). That’s nearly six times Beijing’s official minimum hourly wage. “We used to eat only walnuts, and then we saw on TV that pecans are more nutritious than walnuts,” she says.

“Pecans are very good for the brain. We older people should eat more pecans so that we don’t get Alzheimer’s,” Ms. Liu adds. “My husband has cardiovascular disease, and Beijing TV said eating pecans can help.” She has asked her pregnant daughter-in-law to eat two pecans a day because, she says, “pecans are very good for baby’s brain development.”

Pecans offer a case study in how China is reshaping entire industries for its trading partners-and not only by exporting goods made by its low-wage workers.

Nearly $1 of every $5 China spent on U.S. items last year went to buy food of some sort, $16.6 billion worth, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. U.S. exports of goods of all sorts to China more than doubled between 2005 and 2010. Exports of crops and processed foods-soybeans, dairy, rice, fruit juice-more than tripled. Exports of pecans rose more than 20-fold.

“What’s changed in our business?” asks second-generation pecan merchant and sheller George Martin, president of Navarro Pecan Co. in Corsicana, Texas. “The Chinese entered…and they have been getting bigger and bigger and bigger.”

The dynamics are simple. “We’re in a situation of finite supply and seemingly infinite demand,” says Thomas Stevenson, a Georgia pecan grower and merchant. Eventually, more trees will be planted, but a pecan takes eight to 10 years to bear fruit.

For now, life is good for pecan growers, who produce about $550 million a year worth of nuts at today’s prices. Grower Bill Goff sold the entire crop of his 1,800 acres of Georgia pecans to Chinese buyers last year. But he’s not putting the profits into a sports car. Instead, he is buying up another 500 acres of pecan orchards. In Georgia, he says, pecan orchards hovered between $3,000 and $3,800 an acre five years ago. Today, they sell for between $4,500 and $6,000 an acre.

While China’s appetite for pecans has been a windfall for growers, it poses a challenge for pecan shellers-the middlemen who separate nut from shell and then sell the insides to food companies, grocery stories and direct to consumers.

For some shellers, the trouble is simply getting the nuts they need before the Chinese buy them. For others, it’s about coping with volatile prices to avoid profit-reducing squeezes. This can happen if they pledge to sell nuts at prices that turn out to be below market, or if they try to time purchases only to end up buying at the peak.

For bakers and ice cream makers, it’s all pain. “It’s certainly not very pleasant,” says Bob McNutt, president of Collin Street Bakers, also of Corsicana, which has been selling pecan-packed fruitcakes for more than 100 years. About three-quarters of Mr. McNutt’s sales are from fruitcakes, and 27% of the weight of each fruitcake is pecans. Prices of the pecans he buys are 50% higher than any previous peak. Customers, he says delicately, “are not going to be willing…to participate in absorbing the cost.”

In September, though, Collin did raise the price of a 1-lb., 14-oz. deluxe fruitcake by $1.10, or 4.8%, to $23.95, before shipping costs. Mr. McNutt says he’ll decide in May whether to increase prices again. He worries that if he boosts prices too much, sticker shock will lead some customers to go without fruitcake next Christmas.

At Stuckey’s, a seller of snack pecans popular in the eastern U.S., the strategy is to reduce the size of cans, the quantity of pecans in them and the sticker price-but raise the price per ounce. It is also to look to China.

“We’re in discussions to export Stuckey’s pecans to Asia where we know the growing middle class is increasing demand for premium American brands,” says Charles Rosencrans, Stuckey’s chief executive.

Pecans are a peculiar nut. Walnuts and almonds are grown in the U.S. almost exclusively in California; hazelnuts mostly in Oregon. Pecans, in contrast, grow across the South from New Mexico to Georgia as well as in northern Mexico. That means the types of pecans, their growing seasons and the cost of production vary widely. Further fragmenting the market, between 20% and 30% of all pecans harvested in the U.S. are from wild groves, which makes it tough for the industry to estimate the size of harvests and for growers to coordinate.

Also, growers of walnuts, almonds and hazelnuts are organized into groups, or cartels, that can essentially set prices and decide how many nuts to sell and how many to save for the following year. Pecan growers don’t have such groups, and so have no collective strategy for dealing with the Chinese or other unexpected shifts in the market.

Over time, pecan growers and merchants figured out ways to thrive. Because pecans, more than other nut trees, bear heavily one year and lightly the next-and because the nuts freeze well-companies set aside some nuts in cold storage in good years and sell them in the lean ones. …..

Pecans traditionally made their way from U.S. and Mexican growers to the eight or so major shellers in the U.S. In good years, says Daniel Zedan, a long-time pecan broker in Wayne, Ill., the price paid for the nuts would fall and growers would complain “that the shellers had cheated them.” In bad years, growers would demand higher prices, “leading shellers to feel that they had been taken advantage of,” he says. Some businesses prospered, others failed. But overall, growers and shellers kept each other in check.

All this changed when China entered the picture. In 2007, the U.S. had a bumper pecan crop amid a global shortage of walnuts. That pushed the price of pecans below the price of walnuts, which in the nut business is something like the price of gold falling below the price of silver. The Chinese, who grow and import a lot of walnuts, bought 47 million pounds of pecans that year, four times the previous year’s total, estimates pecan broker Mr. Zedan.

Chinese consumers, it turned out, liked pecans, and they were easier to shell than native Chinese hickory and other nuts. Chinese traders mainly buy pecans in the shell in the U.S., ship them to China where they are cracked, often by hand one at time, and then are marinated in a flavoring brine, roasted and sold in the partially cracked shell as a popular snack, particularly during the Lunar New Year.

American shellers complained that selling so many premium pecans to China-the Chinese want the biggest, best nuts-would undermine both the domestic market and export markets in Europe. So they held back orders. China responded by going directly to growers. As Texas A&M pecan expert Jose Pena puts it: “It’s kind of hard to tell a grower not to sell to the highest bidder.”

In 2008, an off year for pecan production, China bought 53 million pounds, more than they did the previous year. And in 2009, an on-year for pecans but not a particularly big one, they bought 83 million pounds, more than all the pecans the U.S. exported to the rest of the world that year. With so little left in storage from the previous year and with the crop later than usual, the demand pushed the price higher.

“A month before harvest,” says Mr. Stevenson, the Georgia grower, “your email fills up, you get phone calls. One of our best [Chinese] customers called my partner here at 2 a.m. looking for nuts.”

In 2010, the price went higher still. The price of the size of nuts favored by the Chinese-“junior mammoth halves,” defined by USDA standards as 251 to 300 pecan halves to the pound-is now at $6.95 a pound, compared to $3.35 just two years earlier, by Mr. Zedan’s tally.

With the Chinese buying so many nuts, exports to other markets have been crowded out. Some domestic buyers have had trouble getting the sort of nuts they want. One sheller went under last year; its plants were sold to the King Ranch, the big closely held Texas agribusiness that got into the pecan business by acquisition in 2006. Another sheller told customers in November it couldn’t honor its contracts.

At Navarro Pecan, the Texas sheller, Mr. Martin frets that if prices keep rising, Americans will simply make fewer pecan pies. At today’s grocery-store prices a pecan pie takes between $5.50 and $7.50 worth of pecans, depending on the recipe.

But he is hardly discouraged. “Adapt or die,” he says. “After four years of being stupid, we look at the Chinese differently-as just another competitor.”

Then he checks his cellphone messages. A Chinese trader has heard that he has a stockpile of pecans and wants to talk.

“It’s the second time he’s called,” Mr. Martin says. Asked if he is planning to return the call, Mr. Martin smiles and says, “Nope. I’m going to wait till the price gets higher.”

-Junting Yolanda Zhang contributed to this article.

Write to David Wessel at capital@wsj.com.

Copyright 2011 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted here for educational purposes only. Visit the website at wsj.com.