redo Jump to...

print Print...

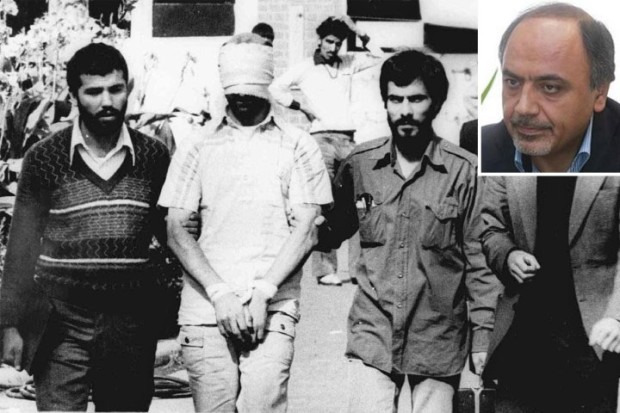

Iran’s new UN ambassador Hamid Aboutaleb took part in the 1979-81 hostage crisis at the US Embassy.

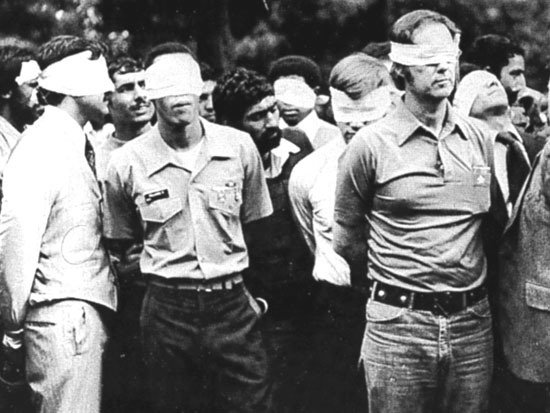

(by Carl Campanile, NY Post) – The White House came under intense pressure Tuesday to deny entry to Iran’s new ambassador to the United Nations because he participated in the humiliating 1979-81 hostage crisis at the US Embassy in Tehran. [The hostages held in Iran between 1979 and 1981 described beatings, theft, the fear of bodily harm while being paraded blindfold before a large, angry chanting crowd outside the embassy, having their hands bound “day and night” for days or even weeks, long periods of solitary confinement and months of being forbidden to speak to one another or stand, walk, and leave their space unless they were going to the bathroom. In particular they felt the threat of trial and execution, as all of the hostages “were threatened repeatedly with execution.” The hostage takers, among other things, played Russian roulette with their victims.]

Former hostage Barry Rosen said it would be “like spitting on us” if the Iranian diplomat – who may have been one of his captors – was granted entry. [“It’s a disgrace if the USG (U.S. government) accepts Abutalebi’s visa as Iranian Ambassador to the U.N.,” Rosen said in a statement. “It may be a precedent but if the President and the Congress don’t condemn this act by the Islamic Republic, then our captivity and suffering for 444 days at the hands of Iran was for nothing,” he said. “He can never set foot on American soil.”]

Americans held hostage in Iran for 444 days (1979-1981)

New York Democratic Sen. Charles Schumer took on the Obama administration by firing off a letter to Secretary of State John Kerry demanding that the US blacklist the new ambassador, Hamid Aboutalebi.

The State Department has delayed making a decision on the touchy issue involving a rogue nation it is trying to bring into the world fold.

“Hamid Aboutalebi was a major conspirator in the Iranian hostage crisis and has no business serving as Iran’s ambassador to the UN,” Schumer told The Post. “This man has no place in the diplomatic process, and the State Department should flat-out deny his visa application. Iran’s attempt to appoint Mr. Aboutalebi is a slap in the face to the Americans that were abducted, and their families; it reveals a disdain for the diplomatic process and we should push back in kind.”

Rosen, one of the 52 hostages held for 444 days in the tense standoff, was incensed that one of his captors might be welcomed into the country.

“It goes against the American grain to grant a visa to someone who was part of a group that tortured American diplomats and military and ruined the lives of 52 hostages and their families. He’s just as guilty as anyone of torture,” Rosen told The Post. “It would be a travesty of justice. It would be like spitting on us.”

Rosen said Aboutalabi’s appointment shows that Iran is testing US resolve. “Denying a visa to him would be a great statement to Iran,” he said.

Aboutalebi was a member of the group called Students Following the Imam’s Line – a reference to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini – that abducted and tortured US personnel attached to the embassy.

Aboutalebi’s precise role during the hostage crisis is not clear. …[In interviews with Iranian media, Abutalebi has played down his role, suggesting he was just a translator. Former hostage John Limbert said he has questions about Abutalebi’s stated role. “I’m not sure exactly what he means by ‘translator’,” he told Reuters. “For whom and where?”]

But that admission placed him smack in the middle of the chilling event.

The State Department has yet to act on the visa application.

Reprinted here for educational purposes only. May not be reproduced on other websites without permission from The New York Post.

Questions

1. What do you learn about the Iranian hostage crisis from the “Background” and “Resources” below the article:

a) When was the Iranian hostage crisis? Who was the president at that time?

b) How many Americans were held? Who were they?

c) Why were they taken prisoner?

d) For how long were they held hostage in Iran?

e) How were they treated?

2. Who is Hamid Aboutalebi?

3. a) Who is Barry Rosen?

b) Why does Mr. Rosen say Aboutalebi should not be given a visa by the U.S. government? Be specific.

4. How did Senator Charles Schumer (D-NY) react to the news that Aboutalebi has been appointed Iran’s ambassador?

5. a) What action has the U.S. State Department taken regarding Aboutalebi’s visa?

b) U.S. State Department deputy spokeswoman Marie Harf declined to comment on Abutalebi when asked about him in Washington on Monday. “We don’t discuss individual visa cases,” she said. “People are free to apply for one and their visas are adjudicated under the normal procedures.” Do you think this is the appropriate response for the State Department?

c) What would you like to hear President Obama say about this matter?

6. Ask a parent what he/she remembers about the Iranian hostage crisis. Then ask: do you agree with Mr. Rosen and Sen. Schumer’s responses or the State Department response? Explain your answer.

Background

The Iranian Hostage Crisis:

In the wake of the Iranian Revolution, anti-American sentiment was widespread in Iran, and the staff at the U.S. embassy in Tehran, which at one time numbered more than 1,400, was reduced to a skeleton crew of roughly 70.

In February 1979, just weeks after deposed ruler the Shah of Iran (Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi) fled Iran, the embassy was besieged and briefly taken over by armed students. One Iranian embassy employee was killed, and a number of Americans were wounded. Iranian authorities assured the Americans that security around the embassy would be improved. However, as Britannica reports:

- In October 1979 the U.S. State Department was informed that the deposed Iranian monarch required medical treatment that his aides claimed was available only in the United States; U.S. authorities, in turn, informed the Iranian prime minister, Mehdi Bazargan, of the shah’s impending arrival on American soil.

- Bazargan, in light of the February attack, guaranteed the safety of the U.S. embassy and its staff.

- The shah arrived in New York City on October 22. The initial public response in Iran was moderate, but on November 4, 1979 the embassy was attacked by a mob of perhaps 3,000, some of whom were armed and who, after a short siege, took 63 American men and women hostage. (An additional three members of the U.S. diplomatic staff were actually seized at the Iranian Foreign Ministry.)

- Within the next few days, representatives of U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Tehran-based diplomats from other countries attempted but failed to free the hostages. An American delegation headed by former U.S. attorney general Ramsey Clark – who had long-standing relations with many Iranian officials – was refused admission to Iran.

- The U.S. responded by freezing Iranian assets and leveraging international support against the government in Tehran.

On November 17, 1979, Khomeini ordered the release of 13 hostages, but the remaining captives were the focus of intense diplomatic and military efforts. As Britannica describes:

- Almost from the beginning of the crisis, U.S. military forces started formulating plans to recover the hostages, and by early April 1980 the U.S. administration, still unable to find anyone to negotiate with in a meaningful fashion, was seeking a military option.

- Despite political turbulence in Iran, the hostages were still being held by their original captors in the embassy complex.

- On April 24 a small U.S. task force landed in the desert southeast of Tehrān. From that staging point, a group of special operations soldiers was to advance via helicopter to a second rally point, stage a quick raid of the embassy compound, and convey the hostages to an airstrip that was to be secured beforehand by a second team of soldiers, who were to fly there directly from outside Iran. The soldiers and hostages would then withdraw by air. However, the operation was fraught with problems from the beginning. Two of the eight helicopters sent for the operation malfunctioned before arriving at the first staging area, and another broke down on the site. Unable to complete their mission, U.S. forces sought to withdraw, during which one of the remaining helicopters collided with a support aircraft. Eight U.S. service members were killed, and their bodies, left behind, were later paraded before Iranian television cameras.

- The Carter administration, humiliated by the failed mission and loss of life, expended great energy to have the bodies returned to the United States. ….

- All diplomatic initiatives in the hostage crisis came to a standstill, and the hostages were placed, incommunicado, in new, concealed locations.

- A U.S. trade embargo, directed against Iran, followed, but it did little to resolve the diplomatic stalemate that the hostage crisis had become. The onset of hostilities with Iraq spurred the Iranians to return to the bargaining table, and indirect negotiations were carried out, with Algerian diplomats serving as back channel couriers for both sides.

- An agreement having been reached, the hostages were released on Jan. 20, 1981, just minutes after the inauguration of President Ronald Reagan. The timing of the event [showed the world that the Iranians were afraid of what Reagan would do to them to get the hostages back when he took office. That is why they released them just as Reagan was inaugurated.] (from britannica.com)

How American citizens taken hostage in Iran were treated by their captors:

The most terrifying night for the hostages came on February 5, 1980, when guards in black ski masks roused the 52 hostages from their sleep and led them blindfolded to other rooms. They were searched after being ordered to strip themselves until they were bare, and to keep their hands up. They were then told to kneel down. “This was the greatest moment” as one hostage said. They were still wearing the blindfolds, so naturally, they were terrified even further. One of the hostages later recalled ‘It was an embarrassing moment. However, we were too scared to realize it.’ The mock execution ended after the guards cocked their weapons and readied them to fire but finally ejected their rounds and told the prisoners to wear their clothes again. The hostages were later told the exercise was “just a joke” and something the guards “had wanted to do”. However, this affected a lot of the hostages long after.

Michael Metrinko was kept in solitary confinement for months. On two occasions when he expressed his opinion of Ayatollah Khomeini and he was punished especially severely in relation to the ordinary mistreatment of the hostages – the first time being kept in handcuffs for 24 hours a day for two weeks, and being beaten and kept alone in a freezing cell for two weeks with a diet of bread and water the second time.

One hostage, U.S. Army medic Donald Hohman, went on a hunger strike for several weeks and two hostages are thought to have attempted suicide. Steve Lauterbach became despondent, broke a water glass and slashed his wrists after being locked in a dark basement room of the chancery with his hand tightly bound and aching badly. He was found by guards, rushed to the hospital and patched up. Jerry Miele, an introverted CIA communicator technician, smashed his head into the corner of a door, knocking himself unconscious and cutting a deep gash from which blood poured. “Naturally withdrawn” and looking “ill, old, tired, and vulnerable”, Miele had become the butt of his guards’ jokes who rigged up a mock electric chair with wires to emphasize the fate that awaited him. After his fellow hostages applied first aid and raised alarm, he was taken to a hospital after a long delay created by the guards.

Different hostages described further Iranian threats to boil their feet in oil (Alan B. Golacinski), cut their eyes out (Rick Kupke), or kidnap and kill a disabled son in America and “start sending pieces of him to your wife”. (David Roeder)

Four different hostages attempted to escape all being punished with stretches of solitary confinement when their attempt was discovered.

The hostage released for multiple sclerosis, Richard Queen, first developed symptoms of dizziness and numbness in his arm six months before his release. It was misdiagnosed by Iranians first as a reaction to draft of cold air, and after warmer confinement didn’t help as “it’s nothing, it’s nothing”, the symptoms of which would soon disappear. Over the months the symptoms spread to his right side and worsened until Queen “was literally flat on his back unable to move without growing dizzy and throwing up.” He was held hostage for 250 days and released on July 11, 1980.

The cruelty of the Iranian prison guards became “a form of slow torture.” Guards would often withhold mail from home, telling one hostage, Charles W. Scott, “I don’t see anything for you, Mr. Scott. Are you sure your wife has not found another man?” and hostages’ possessions were stolen by their Iranian hostage takers.

As the hostages were taken to the plane that would fly them out of Tehran, they were led through a gauntlet of students forming parallel lines and shouting “Marg bar Amrika,” (death to America). When the pilot announced they were out of Iran the “freed hostages went wild with happiness. Shouting, cheering, crying, clapping, falling into one another’s arms.” (from wikipedia)

Resources

Read a 2012 commentary on Iranian attacks on U.S. citizens:

studentnewsdaily.com/editorials-for-students/irans-unrequited-war.

Read a December 2013 daily news article on the former hostages reaction to a nuclear deal with Iran:

studentnewsdaily.com/daily-news-article/former-hostages-react-to-irans-nuclear-deal

Daily “Answers” emails are provided for Daily News Articles, Tuesday’s World Events and Friday’s News Quiz.